► Kenya Science Teachers College (KSTC)

► EPILOGUE

Saraswati, the goddess of learning, knowledge and wisdom. She is mentioned in the Rig Veda and the Puranic texts several thousand years BC.

My photo taken after 51 years, of the place where I started with my first day in school, the Brahmo Samaj in Mombasa, which is now rebuilt somewhat.

Below, also my brother Vasant at the same place and time.

The railway station near where we lived at that time. Railway stations were exciting and exotic in those days.

Only once in my lifetime have I cried in connection with going to school. That day was some day in 1954, when we were living in a house situated near the railway station in Mombasa. My father, in conjunction with my elder siblings, decided that it was time for me and my closest elder brother Vasant to begin the nursery school education together. My mother was, like most Indian women there, a housewife, and we had never gone to any daycare center or any day mother.

What we had heard about schools in general was that they had strict environments, requiring a large amount of obedience and discipline, and that teachers could give the pupils corporal punishment. Of course, this was not a place that one looked forward to! This elder brother of mine had not yet begun nursery school before me because it was not uncommon then that parents waited until they had manageable economy before sending the child to school. It cost money to go to school.

In any case, it had been decided that the two of us were going to begin the nursery school on that monday. On monday morning, then, my father looked at us with strict eyes and said that we should come with him to the nursery school, which was about fifteen minutes' walk. Neither of us wanted that, and we resisted verbally. My father could be strict when he had to, and could even become very angry and give a slap at times, but otherwise I must say that he was a very warm-hearted person and easily felt compassion for persons who were less fortunate.

My fantasy before I had begun school, about the school environment.

So the choice we had was either to accept definitely a slap from my father at once, or instead take the risk of perhaps obtaining one from a teacher sometime in the future if we went to school. So my father walked first, and some ten meters behind him walked my elder brother crying and protesting (remember he was my elder brother and had to take the lead), and about ten meters behind him, I walked dragging my feet, also crying and protesting.

We came to the "school", which turned out to be a community center called Brahmo Samaj, and were greeted by a kind man and a kind woman. After registration, the woman took us to sit down on the floor of a hall, where there sat many children in our age, who were not crying but were rather content. We received a slate and a chalk each, the teacher wrote down in Gujarati 1, 2, 3, and our job was to repeatedly rub along these numbers so that we learnt to write them.

Soon it was time to sing some spiritual and soothing songs together, when a man played harmonium. Then again after a couple of hours or so, there was a recess for half an hour. And we were all given nice warm food and snacks, and tasky milk-shake, by very kind teachers. Our earlier conception of schools being unpleasant disappeared. The next morning, we both got up early and eagerly went back to school, this time at a brisk pace.

WELL, there are many other episodes regarding my education that will be written on these pages. But right now, let me summarize what has happened during the years since I began my first day at the nursery school. After high school, I went to the Kenya Science Teachers College(KSTC) in Nairobi to get a diploma in teaching, and then emigrated to Sweden after teaching shortly at a high school. In Sweden, I first studied mathematics and natural sciences, and I wrote a thesis for a PhD in mathematical statistics in 1979 at the natural sciences faculty, and then qualified for the academic title of docent in mathematical and genetical statistics in 1989. I also studied at the medical school, and in 1999, I wrote a doctoral thesis for Med Dr in psychiatry at the medical faculty, and in 2001 I qualified for the title of docent in epidemiological psychiatry. I became a certified physician in 1988. I then chose psychiatry for my specialization, and in 1993 became a specialist/consultant in psychiatry.

The different research areas I have pursued during the course of the years is discussed elsewhere on this site.

Primay and High Schools (1955-1965):

During the 10th century, arabs settled along the coastal areas of Kenya, who came in dhows by the monsoon winds. It was not until the 19th century that the british appeared in significant numbers. Kenya became a british colony in 1920, and it obtained independence in 1963.

The education system of Kenya when I went to school was characterized by the british education system, modified in some ways to accomodate for the different ethnic groups that were found in Kenya.

So there were schools for europeans, other schools for asians, others for arabs, and still others for africans. An advantage of this was that the schools could accomodate to a greater extent culture-specific teaching; so in the asian schools my mother tongue gujarati was taught, and history encompassed more about Indian history. Within the first couple of years, however, all the more English was introduced and in the final end considered to require an obligatory pass in English in order to be considered to be promoted to a higher level.

The school system consisted of standards 1 to 7 in the primary school, and forms 1 to 4 in the secondary (high) school. Passing this would give the student an "O level" (Ordinary level) certificate. Optionally, if the parents had economical resources and an academic attitude, then one could study two more years at high school to get "A level" (Advanced level) certificate.

The school system was presumably not completely British oriented. For example, the milleu and psycho-social environment that one sees in the British movie "If...(film)" could perhaps be found to some extent in the european schools only, which I realized when I taught at such a former european school when I had qualified as a teacher in 1969. Most teachers in the asian schools were asians, and likewise for the other ethnic groups.

Technical High School, Mombasa

The crying that I mentioned at the beginning of this page was, in a way, not groundless. Most of the teachers throughout the school years were likeable, but there were a few teachers who had a habit of employing corporal punishment often. An unfortunate side of this was that they picked on certain pupils again and again. In retrospect, I think that they were getting out their aggression or stress on these miserable pupils. They picked on pupils who did not have good grades. I hope I am not being immodest when I state that I usually had good grades, and so I was seldom a victim of such teachers. I was rather lazy and often did not complete my assignments in time, but somehow the teachers tolerated my behaviour to a large extent, since when the exams came, I did very well. I did receive occasional slaps, or hits on my fingers with the ruler, but they did not inflict any noteable psychological distress. But for these pupils, going to school must have been a constant torment.

A very sad incident I remember was when I was in standard 2 (age 8). One of the pupils had been evading school for some time, giving different excuses. He did not submit the fees that were due, and had presumably said that his parents were economically in a tight situation, and that the fees would come later on. One day, after having been away from school for a few days - he must have run out of excuses - he told the teacher that his mother had died and that he had been involved with the funeral activities. I learnt about these details when late one morning, in came this pupil with his father (it was unusual to have parents coming in like that), and I understood that the whole thing had been agreed to by the teacher. The pupil was asked to stand on a table in front of the whole class. Then the father pulled down his shorts and made him naked, and started to cane him. He caned the poor boy many times, explaining to the class that his son should be ashamed, and that his mother was in fact still alive. The teacher seemed to have been a part of this conspiracy.

There is another incident which showed that teachers during those days were not aware of certain difficulties that nowadays are wellknown. When I was in standard 7 (age 13) at the beginning of a lesson in English, the teacher wrote PARACHUTE on the blackboard. Then he asked one of the pupils sitting in the middle of the class to stand up, and then, "Dinesh, can you pronounce what I have written on the board?", and to our surprise, Dinesh said, "Piechart". "What?", screamed the teacher, "try once more ". And Dinesh got scared, looked carefully at the word on the board again, and said "Piechart". The teacher got angry and walked to Dinesh, gave him a slap, and said, "Go and stand near the blackboard, and say the word". Dinesh was really scared and did not understand why the teacher was punishing him, since the word he saw was "Piechart". He walked timidly to the blackboard, frightened, cast a glimpse at the blackboard, and looked back to see if the teacher was behind him planning for one more slap. And said, "Piechart". He received one more slap, and the poor boy was so scared that he could not think or concentrate. He squinted, and said softly, "Piechart". So the teacher had to ask him to read each letter at a time, and then he subsequently said "Parachute". Well, Dinesh was short-sighted, which gave rise to the whole incident!

Makupa Primary School, Mombasa (above).

Kenya Science Teachers College (KSTC) (1966-1968):

I had studied high school upto form 4, and it was time to decide if I should continue studying at high school to obtain the A-levels (Advanced levels) in form 6, or if I should look for some job, or something else. Continuing at school would for my family mean paying further tuitions. The time was February 1966, and I was 17.

Actually, it was not uncommon then that young indians went to England (London) for further studies after form 4 to become chartered accountants (CA). This is because the way to become a CA was that the student had some job as an apprentice at a company, and studied during the evenings and some odd days. This meant that the students working for a CA were economically self-supporting. My elder brother Vishnu had already left for London in July 1965 (and subseqently another elder brother too in 1967). So I applied to the British Embassy in the beginning of 1966 to move to England, but was refused, because I had a passport stamped "British Protected Person" and not "British Citizen". The indians living on the coastal strip including Mombasa were given a time limit upto 1964 to apply for British citizenship for a small fee, but I have learnt afterwards that my parents did not do it for the "younger siblings" to save money.

My eldest brother Mahesh has always advocated higher education. He was himself very bright at school, but when he was in his mid-teens, he had to quit school in order to help my father earn money to support the family, which was growing bigger all the time - we are 8 brothers and 2 sisters, and Mahesh is the second eldest. My father, who had gone to school only a few years in his childhood in India, did not see the beauty or feasibility of higher education to the same extent. After coming to Kenya from India in his early twenties, he had worked hard as an errand-boy with different shopkeepers and businessmen who were the ones with money and power. Persons who had successful professional positions requiring high education, were the "whites". In my father's perspective, even if I studied upto form 6, what then? It was expensive to go to the university, and how can one be sure that I would become a successful professional after my family had struggled to financially make university education possible? My father had by then, with the help of Mahesh and other siblings, managed to rise up to having a small shop (or kiosk). And he was wishing that we would some day join hands with him in the business area instead.

It so happened that one of my former school teachers bumped into a brother of mine and said that they had had a visit by a Swedish man from Nairobi, who was travelling around to schools in Kenya, desperatly hunting for students who would like to start studying at a newly opened college called Kenya Science Teachers College (KSTC). The course was to begin in a month's time, with duration three years, and gave a diploma to teach at high schools. There was no tuition fee, the books and education material were given free of charge, it was a boarding school providing boarding and meals free for the student, and moreover, the college gave a small number of shillings as pocket money every month!

It may sound surprising that this Swedish man had to hunt for students, to a college with so generous conditions, but I have been informed afterwards about what actually had happened. The governments of Sweden and Kenya had agreed to start this college as a part of the swedish foreign aid program (SIDA, then called Swedish International Development Authority). The large complex buildings of KSTC were in the planning stage, and would be ready in 1968. However, it had been decided that the college would start in temporary buildings already in March 1966, and all the teachers would be Swedes during the first years until educated Kenyan counterparts were available. Brochures of the college had been printed, and were supposed to have been sent to the high schools long before the end of 1965 to recruit the students. But due to some bureaucratic mishap, the brochures had ended up in some storehouse in Nairobi! So when the deputy headmaster came around December 1965, this mishap was discovered, and so he had to travel around to inform the schools.

For me, this news about the KSTC emerged as a rescue! Free further education, and also free boarding and lodging! There was only one minor problem, that it was a teacher training college, and although high school teachers were respected, they were not considered as educated professionals. There was also a saying among those pursuing education, that "if you have some education but do not succeed in higher studies, you can always become a teacher and support yourself." However, it was implicit in the description of KSTC curriculum that the level of education in science subjects would roughly correspond to the "A levels". Thus, the solution to join KSTC in Nairobi satisfied both my brother and my father - I would get a higher education and at the same time obtain possibilities for a reasonable livelihood by becoming a teacher.

President Jomo Kenyatta laying the foundation-stone of KSTC in October 1966.

I was a British Protected Person and not a British Citizen, which made it impossible for me to move to London to work to become Chartered Accountant..

"The Swedish man" Sven Nilsson, deputy headmaster, who travelled to high schools desperately hunting for students...and the unbuilt but planned KSTC

During the beginnings of the construction of the new KSTC buildings in 1966 (I am standing on the left).

President Jomo Kenyatta at the inauguration of KSTC in October 1968.

My period at the KSTC during the three years 1966-1968, beginning at age 17, was pivotal for the rest of my life in very many ways. Coming away from home and staying at a boarding college was in itself instructive. Cooking food or doing the dishes was not required, but I had to wash my clothes every week by hand, and iron them, which was a relatively new experience for me.

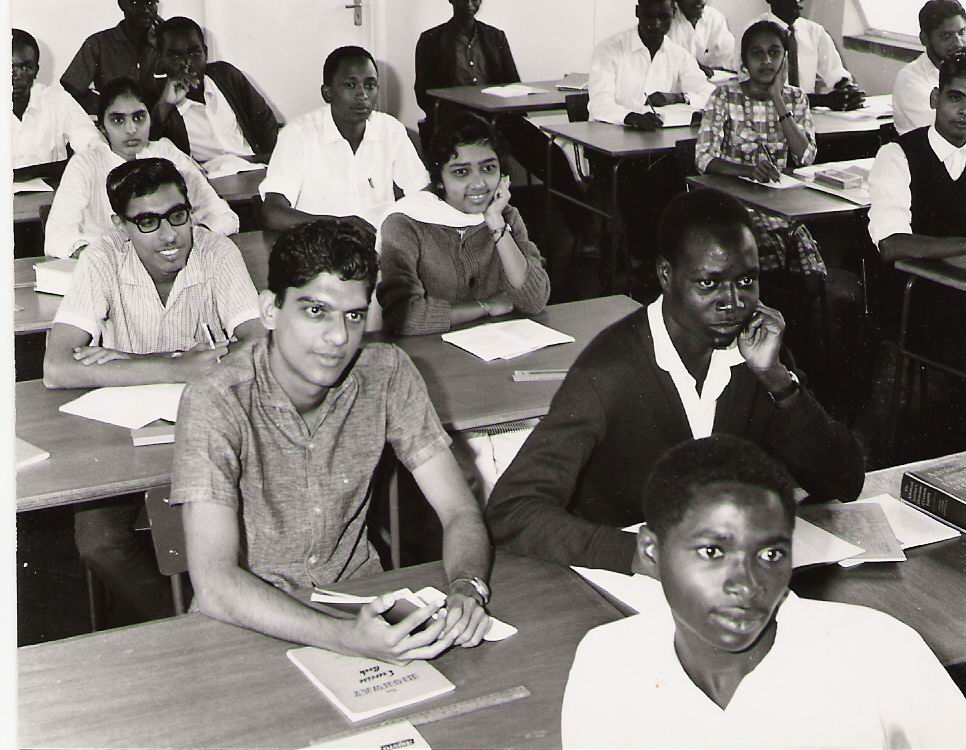

A more important change was that for the first time, I had co-students of African origin also, which I had never had before. I had never met africans in such a context and got to know them closely like I did here. Here were students from all over Kenya, belonging to different "tribes" and speaking different mother-tongues. Even these different tribes had differences in their traditions and experiences. Moreover, this was the first time I had female students as my class-mates.

Earlier in my life, the Europeans I had come in contact with were only the British, since a small number of teachers at the asian schools were british. They belonged to the british ruling class, and at times they could express opinions and perceptions that were patronizing. For example, there was this Mr Wright, our teacher in metal work at high school, who had earlier served the british army and had crashed down from an aeroplane, survived but became hump-backed. He used to lecture us on how thankful we asians should be because the british had been our protectors in India during the war. When he instructed us on using the file (tool) to construct a square in metal, he said he wanted to see a british square (straight edges, and right angles), not an indian square or a chinese square. Then there was this Mr Lewis, who was less serious and friendlier, who used to say that one needed a square mouth to pronounce our indian names. Incidentally, he once went to a party serving spicy indian food, and a couple of days later he told us that he now knew why indians use water instead of toilet paper when visiting the toilet!

All the teachers at KSTC were Swedish (europeans), but I learnt here that there were differences between europeans and europeans. These Swedes were humble, eager to learn about the Kenyan African and Indian cultures and respected these cultures, and were generally not partronizing. I had had an inferiority complex towards europeans, which diminished substantially after having been at the KSTC.

The college years also taught me of the western living style. At my indian home, my elder siblings and parents usually ate food with their fingers or hands, at times complemented by a spoon, and a spoon was something I usually employed. I had heard about and perhaps seen the fork and knife combination, but had never used it. I had heard that eating with your fingers or hands was not "civilized", and I was prepared for this change. So the evening before the first breakfast, I discussed with an indian room-mate about how one should eat the slices of bread that were served. Do you use your hand or do you pick it up with your fork and then cut it with the knife? We were not sure, so we said that we would observe "Agapito" at the breakfast table, and see how he did. Agapito was a goan boy classmate, and we knew that the goans, although indians, usually lived with a western style at home and spoke english at home. So if he eats the bread with his hand, then it should be alright, which to our relief he also did at breakfast! Another noteable change for us was to use the western toilets instead of the eastern toilets we had at home, where we squatted down - after having used western toilets, I detest the eastern ones.

The education at KSTC was in science subjects - mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, geography - and english and some wood work. It was felt as if we had leaped forward a large distance in the educational system. The books were modern, the contents were at the frontier of science, and the teaching methods were refreshing and encouraged independence. In fact, some of the ways of presenting science in the books were so profound that initially, some of my classmates did not quite appreciate them. For example, a chemistry book started by explaining how the scientific mind works, and told the story of a boy lost in the jungle, who wanted to make fire. The boy went out and collected objects he found lying around, and tried to burn them. The wooden branches he had collected burned, but not the other objects. So the boy concluded that cylindrical objects burn. So the next day he collected only cylindrical objects, like branches, but also abandoned bottles and tins, and cylindrical stones. He found now that the branches burned, but not the other objects, and so he modified his previous hypothesis and said that cylindrical things that are brown burned. And so on... I still recall my classmates telling the teacher that such stories were childish and insulting to their educational background, and that the book was too simple for their level. After a few weeks' studies, though, they had difficulties in keeping up with the contents of the textbooks.

During the same years as I was at the KSTC, I was developing from being an adolescent to being a young adult. This transition brought with it a lot of emotional and intellectual challenges. I obtained a lot of support and advice from some of these Swedish teachers during the evenings when they were "housemaster on duty". Particularly it was Lars-Erik Björkman, who made it possible for me later to emigrate to Sweden, and also Andrejs Dunkels, my mathematics teacher. It was at KSTC that I learnt to hold a girl in my arms and dance (western) at the dancing parties that the college organized. We had informal dancing lessons at the college certain evenings.

Myself at KSTC (left), and celebrating the Swedish midsummer festival at Ngong Hills near Nairobi (right), both in 1966.

A field study excursion from KSTC, camping at Silversands, Malindi, Sept 1967.

My registration as a high school teacher in Kenya, 1968.

The pioneering Swedish teachers at the start of KSTC in March 1966.

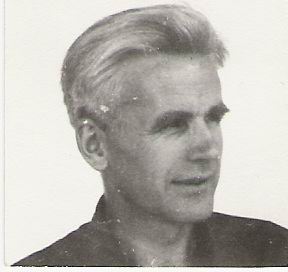

Lars-Erik Björkman (1922-1995) (above, KSTC physics) made it possible for me to emigrate to Sweden in August 1969 and commence university studies.

Andrejs Dunkels (1939-1998) (above, KSTC mathematics), who aroused my appetite for mathematics. Subsequently, Andrejs became renowned from Sweden for his drawings called "footies", which he employed when teaching mathematics or statistics.

With classmates at KSTC, strolling (above) and in a classroom (below).

Dancing with Bharti at an evening dance at KSTC (the couple far left).

A field study excursion from KSTC, at Gedi ruins beyond Mombasa, Sept 1967.

My final certificate from the KSTC, 1968.

Uppsala University (1969-1971):

It was a fantastic and remarkable feeling when, on 20 August 1969, I landed at Gothenburg's airport in Sweden. And the feeling was still more fantastic when, after a week, I stood at the doorsteps of the main building of Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. I had obtained financial support to start studying at Uppsala University!

Uppsala university's main building, 1970.

Above the entrance of Uppsala university is an inscription of the Swedish philosopher-author Tomas Thorild (1759-1808), saying (free translation):

With regards to how success in the society is often attained by people, I have at times thought that a continuation with one more line would be apt: To convince others you are correct is greatest |

My first receipt of paid fees at Uppsala university, September 1969.

During my years at the KSTC until graduation with a teacher's diploma in December 1968, my appetite for further education had grown all the more stronger. I had discovered that mathematics and science were really fun, and there was a very positive attitude from the swedish teachers towards going ahead for university studies. Firstly, there was a pronounced need to obtain kenyan counterpart teachers to replace the swedish teachers at KSTC. Sweden had been carrying out scholarship programs for some years prior to the start of KSTC enabling Kenyans to study in Sweden, and now there was in progress a discussion for the recruitment of the counterparts. Secondly, the strong pioneering spirit that was prominent at KSTC among the teachers, was conducive to helping us progress successfully to obtain higher levels. During the 1960's, the economical situation in Sweden and the western world was very bright, and at that time the resources of the world seemed unlimited, and the younger to middle generations in Sweden had become very progressive and radicalized, and most importantly, globalized in their attitudes.

My teachers were in agreement that I should definitely go ahead with university education, and they saw a strong potential in me. But my application for a kenyan citizenship had not been processed although submitted five years earlier (this was the case for many persons of indian origin in kenya at that time). I would get an admission to study at Nairobi university, but I would not get financial support like the kenyan citizen students were entitled to.

Lars-Erik Björkman did something great for me that I still find it difficult to express my gratitude for. He had returned to Sweden in mid-1968, and he had said that he would explore the possibilities available to enable me to emigrate to Sweden for further studies. In Sweden he took up my case at a national meeting of high school physics teachers in Sweden, and told the story of my difficulties in pursuing university studies due to the circumstances described. There was a spontaneous suggestion from quite a few of the participants, that maybe they would contribute a sum of money each for three years to sponsor my studies in Sweden. Furthermore, Lars-Erik also took up this issue at a meeting of the post-KSTC teachers in Sweden, and received a similar response. So a stage was set where money would be committed by individuals to sponsor me for three years' studies at Uppsala university. The Swedish students were (and are) entitled to study loans from the government when they study at the university, so in the same vein, it was decided to establish a bank account called "Chotais studiefond", from where I would borrow money during my studies, and pay back later like the swedish students do. (However, by the end of the three-year period, I was told that I could consider it as a scholarship, and instead try to do something good for developing countries in return.)

[In fact, objections were raised when Lars-Erik was planning to help me come to Sweden, by two influential persons, a former KSTC headmaster and a manager at SIDA (then called Swedish International Development Authority). They said that this move could be construed by the Kenyan government as an activity of the Swedish government to "brain-drain" from Kenya, the country whose govenment did not give me citizenship and thereby made it impossible to study at the unversity in Kenya (apparently, Catch-22 can appear in various disguises!)].

Wonderful, free, student life in Uppsala, living in student hostels and having fun!

Some parties required formal dress (above top), even though they could sometimes be topped with fancy supplements (above bottom).

Political demonstrations, particularly on 1 May, were a part of Uppsala students' activity in the 1960-70's (1970).

Some of my physics books during studies in Uppsala.

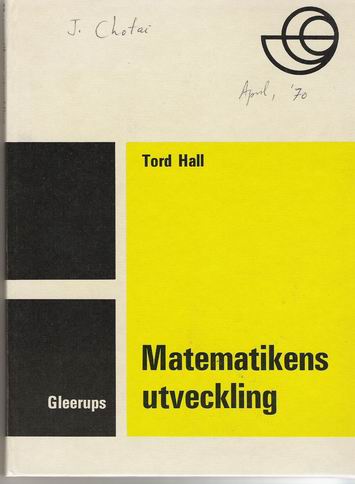

Some of my mathematics books during studies in Uppsala.

Outside my student hostel, with the Uppsala cathedral behind, 1970.

My first student ID at Uppsala university, September 1969.

On 30 April, to signal the coming of the spring, the students take their student caps on and collect at the library Carolina Rediviva and Gunilla klockan, to run down the street (above top) and celebrate along the river Fyrisån (above bottom) in Uppsala (1970).

A good part of the student life in Uppsala consisted of parties with fun and informal clothes (1970).

With due respect to the political activities and the social activities, the main aim of my being in Uppsala was nevertheless university studies. In fact, Lars-Erik had said to me that when he was arranging for my possibilities to come to Uppsala, he did not doubt my academic abilities, but he was a little hesitent regarding my abilities to pursue further studies efficiently when I would be left alone at the university with all the temptations and freedom that the students had, especially in those days. There were quite a few swedish students who studied haphazardly without getting proper degrees, and took study loans for as long periods as they could. As mentioned earlier, the economical outlook in Sweden and the western world was very optimistic during those years (the oil crises came later on, first in 1973, creating the 1973 world oil shock and putting a stop for the economic boom). I started studying mathematics for one year, then studied physics for one year. I also studied some numerical analysis and the computer language Fortran in parallel. All the studies and textbooks at the university were in Swedish. Thus, during the first year, I also had to study the Swedish language, and although some had suggested that I spend the first term (semester) studying Swedish fulltime, both I and Lars-Erik were in agreement that I would pursue the Swedish courses in the afternoons parallel to university studies in mathematics. We reasoned that the logic and symbolics of mathematics constituted an international language anyhow!

My certificate of proficiency in Swedish. But then another development had been taking place in my social life. After a year in Uppsala, in the summer of 1970, I went to London for a vacation. There I met a Swedish girl called Inger who had come there on a vacation from Gothenburg (and she subsequently became my wife and we stayed together for 20 years). On return to Sweden, we kept contact with each other between Uppsala and Gothenburg. She was nearing completion of her nursing course. She said that she had always dreamt of going to live in Norrland for a couple of years - norrland is the northern part of Sweden which contains Umeå. I had no other attachments to Uppsala than university studies, and Umeå in norrland had a younger but nice university, where I could continue my studies. Furthermore, in Umeå lived at least two former teachers from KSTC including Andrejs Dunkels. So we decided that we move to Umeå temporarily, she from Gothenburg, and I from Uppsala. She got a job as a nurse, and I enrolled at mathematical statistics department of the university. |

Some of my mathematics books during studies in Uppsala.

Bye, bye Uppsala ...

Umeå university (from mid-1971):

I came to Umeå after the summer of 1971, with a vision of staying here for a few years, but I still live in Umeå since then. I continued the university studies and commenced mathematical statistics in order to obtain BSc (Fil.Kand.) in 1972. Then, luckily, I was offered a parttime job of teaching (amanuens) at the dept of mathematical statistics by Professor Gunnar Kulldorff, and so I chose to pursue further studies in that subject. I registered as a doctoral student in that subject in 1973, the same year that my first child Frank was born in March.

In 1974 I wrote a masters thesis (MSc) in mathematical statistics on the subject of sampling from a population on successive occasions (pps sampling), and utilizing information obtained from the previous occasion. I thereby published my first scientific paper in 1974 in an international journal. My research is discussed on a separate page on this website.

I had some very good friends from the Middle East, and one of them was a medical student. At the back of my head I was all the time pondering on how I could in future be of use to developing countries. Somehow, my feelings and memory of having obtained so much help from others at crucial moments in pursuit of higher studies, made me a little restless and I was constantly questioning myself if I was doing anything worthwhile. Maybe, this is what most young adults go through in any case.

My friend, the medical student, said that it was interesting and very worthwhile to study medicine, particularly if I was pondering on serving developing countries in future. As a student, I have always been curious and interested in all sorts of subjects, and often read and pondered on stuff other than what was required in the courses I was taking. I could often get intellectually engrossed in diverging subjects, which many times resulted in not succeeding in my exams in time.

So I applied to the medical school for the program leading to becoming a physician. It was very difficult to get a place in this program due to a lot of competition, but I was lucky! During those years, the government had decided to reserve a small percentage of the seats in the medical program for persons who had other experiences and education in the society rather than coming directly from the high school. The idea was to allow others with practical or diverse experiences to enter the medical school. So I obtained an admission to the medical school.

When I informed my doctoral supervisor in mathematical statistics, Professor Gunnar Kulldorff, he was taken aback. He has always been kind and caring to me, and had high hopes for me to write my thesis in that subject. He said he was surprized that I was moving into another field when so far I had been relatively successful in mathematical statistics. I put forward to him my idealistic thoughts about working in developing countries in future. He said that if I worked as a physician, then I would help one person at a time, whereas if I did research successfully, then I would be advancing the scientific field to the advantage of many. Ambitious as I was, I suggested that I would pursue mathematical statistics in free time and in summers and will eventually write a doctoral thesis. He was sceptical about my optimism, since two other students had earlier given up the subject and never came back once they had started the medical school, and he said, "then you will be the first one to do what you say".

So I started the medical school in January 1975, and had to begin taking study loans that I by now was entitled to, like the Swedish students. In May 1975, my second child Erika was born. Prof Kulldorff was very helpful and supportive, and he made it possible for me, by parttime scholarships, to pursue doctoral studies in summers instead of having to take up some other summer jobs.

In contrast to mathematical statistics, the medical studies were demanding in a different way - they involved a lot of facts to be crammed. The first term (semester) was anatomy, and this was almost entirely a matter of learning by heart the different, big as well as minute, parts of the body. Learning by heart, or cramming, was actually not compatible with my personality.

I had not realized before that every minute part of the body can be given a name...

I remember remarking during a coffee break to a professor in mathematical statistics, that when I was working with the doctoral studies in mathematical statistics in 1973-1974, I was glad that at last, I had got away from the procedure of sitting for traditional exams, where one has to reproduce things from the memory.(It is obvious that I detest memorizing things!) Instead, I had embarked on a long (five and a half years) medical course, where there were many small and big exams, and where learning by heart and cramming was the norm.

When I had studied medicine for three years, I had also made progress in the doctoral studies in mathematical statistics to such an extent that it would then not be a bad idea to put a full-fledged effort on my doctoral thesis. Also, the cramming in the medical studies was, in comparison, far less attractive. In Sweden, one is allowed to take breaks from the medical school and return later. So Prof Kulldorff offered me a job at the department, and I took a break from my medical studies (to which I later returned in 1980).

I wrote and defended my doctoral thesis in mathematical statistics in June 1979. Then again, I was tempted to and offered to, continue for a career in that subject at the university. But my friends and relatives in Sweden had a lesser appreciation of the academic subject of mathematical statistics, but they had high opinions about becoming a physician. And one obtained better economical circumstances as a physician than as a university researcher and teacher. (Not until one had successfully completed the medical studies, though!!) The argument was, that when I had done three years of medical school, how can I just leave it behind me? Moreover, at the back of my mind, there still lingered the idealistic thoughts about working in a developing country some day!

So I was convinced that the relatively appropriate course of action was to go back to the medical school and continue where I had left. A few months after I had gone back to the medical studies, I was phoned by Professor Lars Beckman, dept of medical genetics, and he recalled that I had expressed an interest to go deeper into medical genetics when I took that course some years back. He asked if I still was interested, and I was delighted. It is not unusual for medical students here to have such parttime assignments at a department parallel with the studies. This affiliation enabled me to get interested in the newly developing field of genetic epidemiology, which is roughly concerned with gene-environment interactions and genetic risk factors at the population level.

In 1981, the national research councils in Sweden felt that Sweden had too few epidemiologists (persons who study disease risk factors in the society as a whole), and so it was important to send some scholars abroad for a year to train themselves in epidemiology, and thereby increase the competence in this field in Sweden. I applied to train in genetic epidemiology. I must have formulated the application very convincingly, and pointed out the exciting research developments that were taking place internationally, because I was chosen among the four successful candidates from over forty applicants. The research councils provided for a salary, travel expenses for the whole family, and some extra economical supplement due to increased cost of living by staying abroad.

So in January 1983, I and my family (wife and three children in ages almost 10, 8 and 2 years) flew to the USA, University of Honolulu in Hawaii, to stay there for the rest of 1983, and for me to train in genetic epidemiology. I learnt a lot about this field and did some research, before we came back to Umeå in December 1983.

On my return to Umeå in 1984, I got a position as a teacher (forskarassistent) in the medical faculty, at the dept of social medicine, to teach the medical students epidemiology, medical statistics, and social medicine. However, after about two years, I took up internship which lasts about two years, and became a certified physician.

Then a question arose as to what clinical speciality I would select to specialize in, leading to becoming a consultant. I weighed between internal medicine, general practice, social medicine and psychiatry, and finally chose psychiatry. The five-year track as a resident finally led me to qualify as a consultant psychiatrist in 1993.

In 1995 I took up a position as senior psychiatrist in "Södra Lappland" of northern Sweden which contains the towns Lycksele, Vilhelmina and Storuman. I was the head of the psychiatric clinic there for a few years and then returned to Umeå university hospital as a senior psychiatrist in 1998.

In May 1999, I defended my second doctoral thesis, this time in psychiatry in Umeå.

From 2003, I was employed first as a senior lecturer then docent (Assoc Prof) and subsequently Professor of psychiatry combined with being a consultant psychiatrist, as described on the page My profession on this website.

The research I have been carrying out during all these years intermingled with teaching, clinical work and studies, is discussed on the page My research.

%20137.jpg)

At beginning of this page, I wrote about how I and my brother Vasant began our nursery school. Above is a picture showing our imagination of what we might look like when we are in our 80's.

Umeå university, with its statue called "norrsken", the northern lights (Aurora Borealis).

Certificate of my masters degree in mathematical statistics, 1974.

... and that one could be expected to cram these.

My doctoral thesis entitled "Selection and ranking procedures based on likelihood ratios", defended on 1 June, 1979.

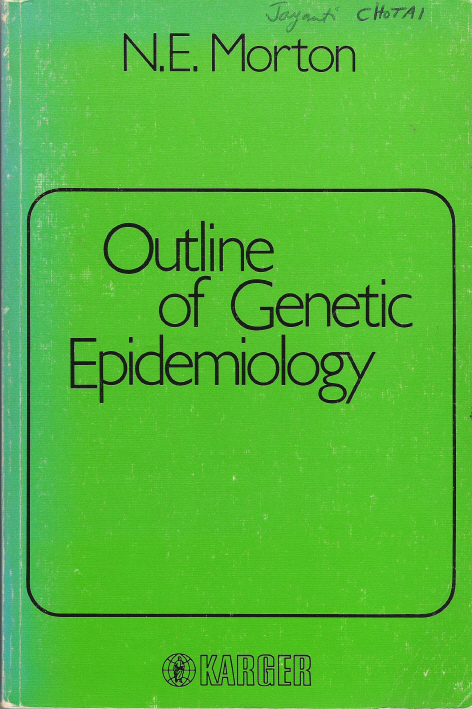

Some books of relevance for my training in genetic epidemiology, 1983.

On our way to Hawaii via Gothenburg, 1983 (carrying my third child Sara who was born in 1981, and sitting besides my former wife Inger).

My second doctoral thesis, this time in psychiatry, entitled "Season of birth in suicidology", which I defended on 28 May 1999.

I have described my education from my nursery school upto where I am now. In retrospect, I feel that I have generally not done any long-term planning, but the different developments have been influenced by many chance events. Many opportunities that I have obtained to pursue my further development, have come along by luck, by me being in the right place at the right time. In spite of all the opportunities that have knocked at my door, I genuinely feel that I have not taken optimal advantage of these opportunities, and I have often found it difficult to "keep my eye on the ball", but instead I have floated around, taking life as it unfolds.

All my education has meant that I have often failed to take due part in my family life, and instead of devoting most of my efforts to develop my family, I have instead used the efforts to educate myself. Looking at my work today, I am sure that one could have arrived there by much shorter and more efficient routes.

Actually, my education is very extensive. On the one hand, I have studied at the natural sciences faculty, first BSc, then MSc, then PhD, and further qualifying to become docent (roughly Assoc Professor) in mathematical and genetical statistics. On the other hand, I have studied the full 5½ years course at medical school, then done internship, and then pursued residency to become a consultant ("specialist") in psychiatry. On top of that, I have defended a PhD thesis in psychiatry, and after that further qualified myself to become docent in psychiatry, and finally professor of psychiatry. But pursuing that much education is nothing I would recommend to anybody. As I said, there are shorter and more efficient routes to come to the stage of doing what I am doing. Moreover, those other routes would most likely lead to becoming a more successful and a more useful member of the society.

I must admit that education has often satisfied my academic curiosity, but at the same time, the constant small and big exams during the course of the years have kept me preoccupied and have hindered me from devoting myself to other duties of life, particularly those related to my children and my former wife.

Not to give a wrong total picture, I must say nevertheless that I have enjoyed my life on the whole, and I have no serious regrets. I think that all the way from my childhood, I have had what others have understood as an amiable personality and an academic aptitude.

To be fair, I did feed my children and change their nappies at times....

► My Kenya

Wonderful memories from Mombasa are the most sustainable treasures of my life!

.... or took a bath with them, or read a book for them.